The word “canon” applied to Scripture means “an officially accepted list of books”. The word is derived from the Greek word Kanon, meaning ‘reed’. A reed was used as a measuring rod, and the word eventually came to mean “standard”.

When we speak of the Christian canon of Scripture we are referring to the universally accepted 66 books of the Bible. 39 in the Old Testament and 27 in the New.

What is important to remember is that no religious body decided what would be included in the canon of scripture, they simply recognised the books that were already accepted as inspired. Geisler and Nix state, “Canonicity is determined or fixed authoritatively by God; it is merely discovered by man.”

F F Bruce, the church historian, stated concerning the canon of 27 New Testament books:

“when the last church council – the Synod of Hippo in AD 393 – listed the twenty-seven books of the New Testament, it did not confer upon them any authority which they did not already possess, but simply recorded their previously established canonicity.”

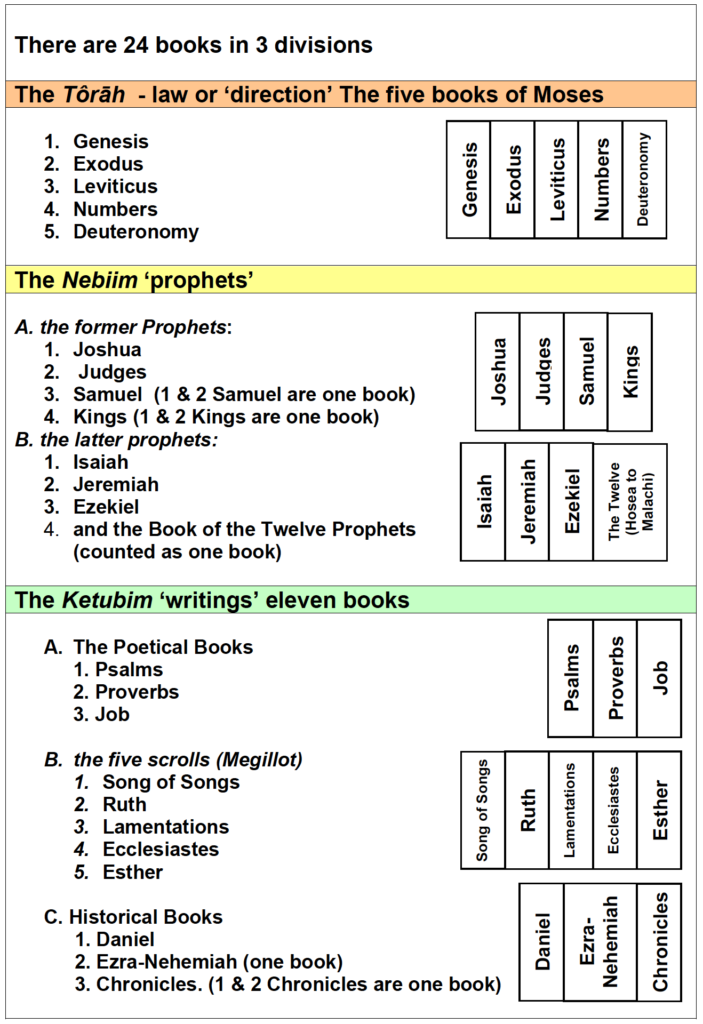

The Old Testament Canon

Tradition says that the Old Testament canon began originally under Ezra, but became definitive after AD70 and the destruction of the Temple. With the Jews scattered, and so many extra-scriptural writings abounding, it became essential to determine which books were the authoritative Word of God. With the rise of Christianity and the circulation of their writings, it also became important to the Jewish mind that these writings be exposed and excluded.

The following table outlines the Jewish Old Testament canon:

The Christian Old Testament canon contains the same books, but we divide Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Nehemiah and Ezra and the minor prophets. The protestant Bible also follows a topical instead of the official order.

We find witness to the official Jewish Old Testament canon in the New Testament. Jesus Himself speaks of the things spoken of Him in the law, the Prophets and the Psalms:

“Then He said to them, “These are the words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things must be fulfilled which were written in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms concerning Me.””

(Luke 24:44 NKJV)

He here indicates the three sections, the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings (here called the Psalms as it was the first and longest book of this section).

Luke 11:51 also indicates an acceptance of the extent of the Old Testament canon when he speaks of the “blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah”. Abel, as we know, was the first martyr to be named in the Hebrew Old Testament order, and Zechariah is the last, recorded in 2 Chronicles 24:21, the last book in the Hebrew canon.

There is also extra-biblical evidence for the widespread acceptance of this three-fold division of the canon by other writers such as Josephus.

We can see that in the Hebrew mind the canon was already in force many years before it was officially recognised at the council of Jamnia in AD90.

The New Testament Canon

Josh McDowell, in his book, A Ready Defense, points out:

“Sceptics often ask: “How can Christians believe to be the Word of God the twenty-seven books designated to be scripture by fallible men at a fourth century council?” This however, does not give a true picture of what took place at church councils concerning the canon. The books included in the canon were already accepted and in general use by the church. As Bible scholar Donald Guthrie describes it, “The content of the canon was determined by general usage, not by authoritarian pronouncement.””

There is sufficient evidence in the letters of the early church fathers, Irenaeus and Tertullian, to indicate that by the 2nd Century, only the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, were in official use. Acts, essentially part two of Luke’s gospel, is also included in these orthodox writings. Doubtless, the epistles of Paul were also accepted as authoritative by this time also. Even in the days of the Apostles themselves, Paul’s writings were considered as scripture, as declared by Peter in his letters (2 Peter 3:16).

As time passed, a proliferation of writings increased which either diverged from the Apostolic teachings, or which claimed to be written by the apostles, but clearly were not. As with the Old Testament canon, it became essential that an official standard or list be formulated based on strict guidelines.

Tests of canonicity included:

- Is it apostolic?

Was it written by an apostle or by someone directly in relationship with the apostles (as were Mark and Luke). - Is it Authoritative?

Did it come from the hand of God? (does the writing bear the marks of supernatural inspiration?) - Is it dynamic?

Does the writing carry life-changing power? - Was it received, collected, read and used?

Was it generally accepted by the people of God?

The twenty-seven books we count today in the New Testament underwent all of these rigorous tests, with 2 Peter, 1 and 2 John, James and Jude and even Revelation encountering resistance from some in the councils that were held. Thank God, however, that the close scrutiny that these books received before being accepted as authentic, gives the reader great confidence as to their reliability in what they report and teach.

The ‘Apocrypha and ‘Pseudepigrapha’

There are also a number of books which constitute a body of religious works that did not pass these tests for authenticity. They abound with details that are inaccurate, whether geographical or historical, and also contain teachings divergent from the apostolic teaching handed down from the disciples of the Messiah.

The ‘Apocrypha’ consists of a number of books that were added to the Old Testament by the Roman Catholic church, but that protestants say are non-canonical. They contain some interesting historical and spiritual works, but none were ever in general acceptance by the wide body of the church.

Jesus and the New Testament writers never once quote the Apocryphal books, and the early church fathers spoke out against them in their letters. The Jewish scholars in AD 90 at the council of Jamnia rejected them, and it was not until AD1546 that the Roman Catholic church gave them full ‘canonical’ status.

Some among the New Testament apocryphal works, (which have never been declared canonical by either Protestant of Catholic religious bodies), rightly deserve the name ‘apocrypha’, which means “hidden or concealed”, as many of them claim to reveal secret or hidden details of the life and teachings of Jesus and the disciples. Among the most discussed is the heretical ‘Gospel of Thomas’.

There is a further body of writings known as the Pseudepigrapha. These are books which attribute their contents to an apostolic author, and falsely claim to be written by true prophets or apostles.

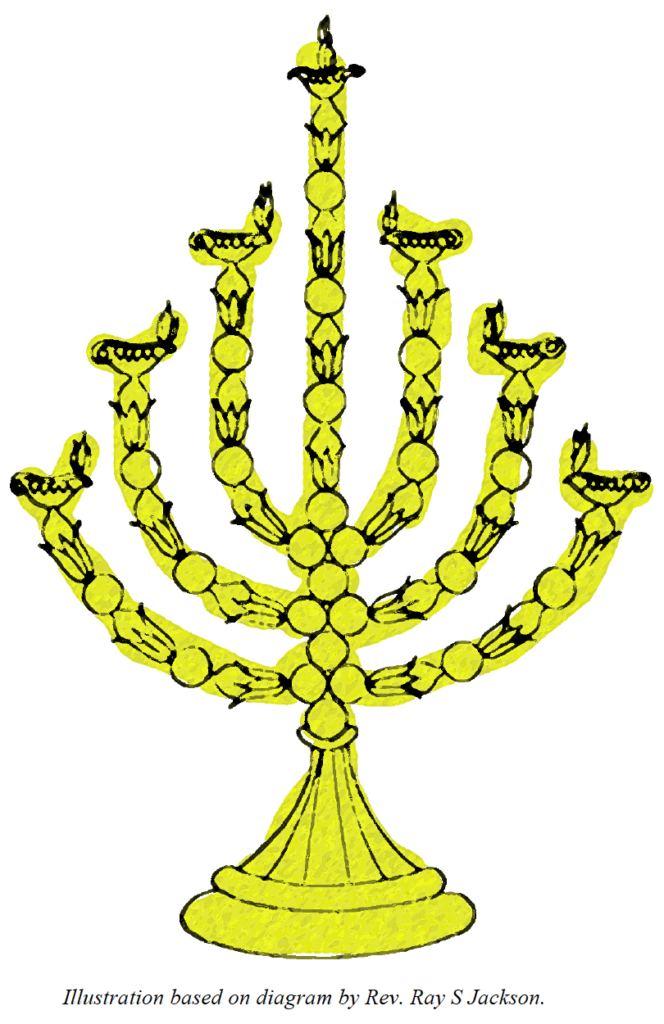

The Light of God’s Word

A further witness of the divine hand guiding the preparation of the canon is found in a surprising place. In the tabernacle of Moses a candlestick was created with seven branches. This candlestick was the only light that illuminated the holy place in the Tabernacle. Today, our only light is the divinely inspired Scriptures, revealed by the Holy Spirit to the heart and mind of the reader. God’s Word is often referred to as ‘light’ in the Bible.

“The entrance of Your words gives light; It gives understanding to the simple.”

Psa 119:130 NKJV

When the bowls, knops and the flowers on the shaft and the six branches are totalled we have a picture of the Biblical canon. There were three groups of bowls, knops and flowers on the three branches on one side (3 x 9 = 27). If we then add the 12 on the main shaft we get a total of 39 (27 + 12 = 39). This speaks of the books in the Old Testament.

The remaining three branches then total a further 27 ornaments, corresponding to the 27 books of the New Testament.

We also note that the candlestick was expressly made from one piece of gold (Ex 25:36). We also have a divinely designed book, with 66 parts unified by one Spirit into one Book.

For more information please refer to Kevin J Connors book, “The Tabernacle of Moses”

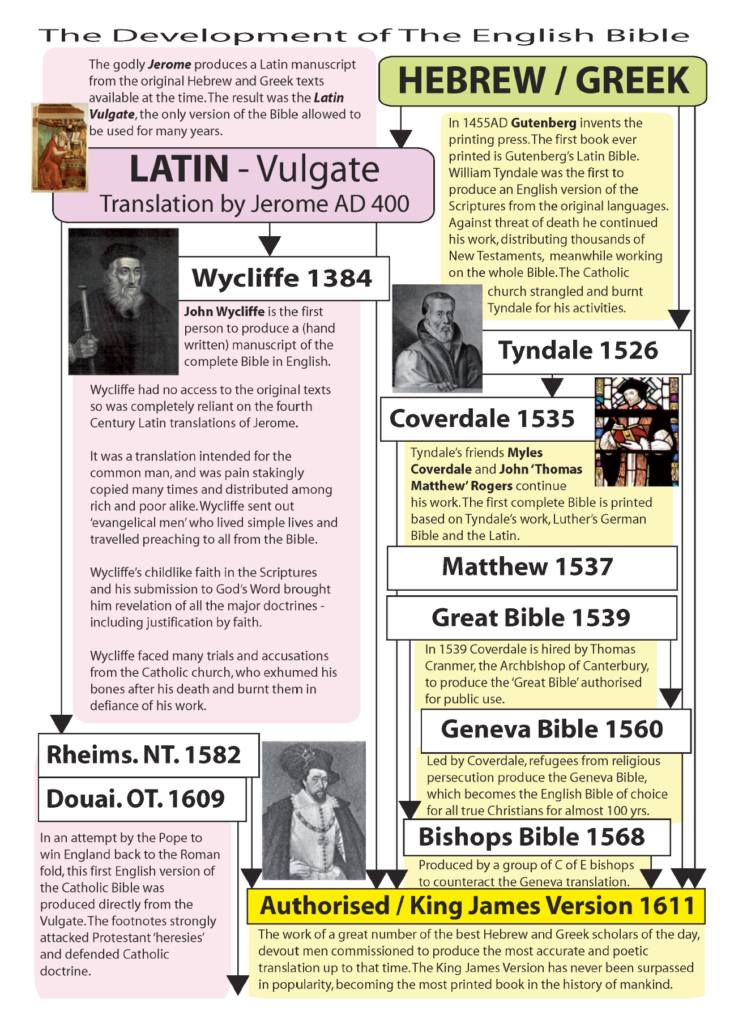

The English Bible

There are many translations available today for use by the modern Bible reader. Some seek to stay close to the original words and sentence structure, others are more concerned with keeping the idiom and general force and meaning of the original. They range from the majestic language of the beloved King James version, to the quirky modern prose of ‘The Message’.

Most versions have some features which can be helpful to the Bible Scholar, but a basic understanding of the differences can be helpful.

For serious study an accepted translation is recommended, the New King James or New American Standard being some of the most accurate modern translations.

Students are recommended to build a library of translations to which they can refer, however, as each can help to aid our understanding of a particular passage. We will consider this in more detail in the next session when we talk about methods of study.

The Overwhelming Preciousness of the Scriptures

We will not here go into minute detail concerning the formation of the Scriptures in the English tongue. However, we do want to stress that many men gave their lives in order that we today could enjoy the scriptures in our mother tongue.

Great scholars like Wycliffe and Tyndale particularly shine out among the pioneers of Bible translation, even, as they were, under penalty of jail or death for their efforts. Wycliffe, heralded today as the forerunner of the Reformation, was the first to produce a version of the entire New Testament in the English tongue. William Tyndale was responsible for the first printed New Testament, translated directly from the Greek. In 1535, Coverdale, who worked closely with Tyndale, then published the first full Bible in English.

Other versions followed before the publication of the Authorised King James Version, in 1611. This was distinguished from earlier printed versions in that a committee of devout scholars, as opposed to individuals, produced it. The King James has become one of the most loved and reproduced books in the history of mankind, and set a standard that all others have either reached for or built upon.

We here present in a diagram the history of these first English translations.